The physicist Freeman Dyson and the computer scientist William Press, both highly accomplished in their fields, had found a new solution to a famous, decades-old game theory scenario called the prisoner’s dilemma, in which players must decide whether to cheat or cooperate with a partner. 8) If kaiser cheats, the gain is $125 and t he present value(PV) of benefit is $250. 9) If Kaiser cheats and punishment for two months is given loss is $127 and the PV of loss from cheating is 254. 10) It is better for Kaiser to cooperate. It is beneficial for the firm to follow two-part tariff strategy. The optimal price is set in such a way that the user fee is charged where marginal cost. But new power plz Hello game maker, I LoVe this game!! But I would like to say a new update idea. First of all, I want 3 new powers. The first power has to be called frozen blast. I want it to slow down or freeze other players and the lvl to unlock it would have to be lvl 34. I also want frozen blast to blast out snow and ice.

Game Theory and Oligopoly Behavior

Oligopoly presents a problem in which decision makers must select strategies by taking into account the responses of their rivals, which they cannot know for sure in advance. The Start Up feature at the beginning of this module suggested the uncertainty eBay faces as it considers the possibility of competition from Google. A choice based on the recognition that the actions of others will affect the outcome of the choice and that takes these possible actions into account is called a strategic choice. Game theory is an analytical approach through which strategic choices can be assessed.

Among the strategic choices available to an oligopoly firm are pricing choices, marketing strategies, and product-development efforts. An airline’s decision to raise or lower its fares—or to leave them unchanged—is a strategic choice. The other airlines’ decision to match or ignore their rival’s price decision is also a strategic choice. IBM boosted its share in the highly competitive personal computer market in large part because a strategic product-development strategy accelerated the firm’s introduction of new products.

Once a firm implements a strategic decision, there will be an outcome. The outcome of a strategic decision is called a payoff. In general, the payoff in an oligopoly game is the change in economic profit to each firm. The firm’s payoff depends partly on the strategic choice it makes and partly on the strategic choices of its rivals. Some firms in the airline industry, for example, raised their fares in 2005, expecting to enjoy increased profits as a result. They changed their strategic choices when other airlines chose to slash their fares, and all firms ended up with a payoff of lower profits—many went into bankruptcy.

We shall use two applications to examine the basic concepts of game theory. The first examines a classic game theory problem called the prisoners’ dilemma. The second deals with strategic choices by two firms in a duopoly.

The Prisoners’ Dilemma

Suppose a local district attorney (DA) is certain that two individuals, Frankie and Johnny, have committed a burglary, but she has no evidence that would be admissible in court.

The DA arrests the two. On being searched, each is discovered to have a small amount of cocaine. The DA now has a sure conviction on a possession of cocaine charge, but she will get a conviction on the burglary charge only if at least one of the prisoners confesses and implicates the other.

The DA decides on a strategy designed to elicit confessions. She separates the two prisoners and then offers each the following deal: “If you confess and your partner doesn’t, you will get the minimum sentence of one year in jail on the possession and burglary charges. If you both confess, your sentence will be three years in jail. If your partner confesses and you do not, the plea bargain is off and you will get six years in prison. If neither of you confesses, you will each get two years in prison on the drug charge.”

The two prisoners each face a dilemma; they can choose to confess or not confess. Because the prisoners are separated, they cannot plot a joint strategy. Each must make a strategic choice in isolation.

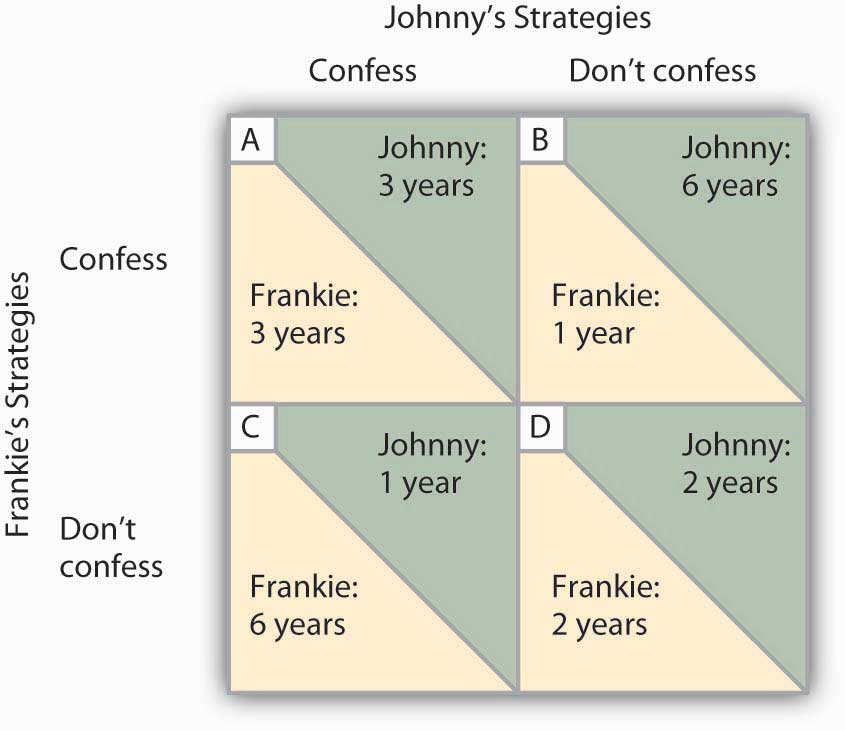

The outcomes of these strategic choices, as outlined by the DA, depend on the strategic choice made by the other prisoner. The payoff matrix for this game is given in Figure 11.6 “Payoff Matrix for the Prisoners’ Dilemma”. The two rows represent Frankie’s strategic choices; she may confess or not confess. The two columns represent Johnny’s strategic choices; he may confess or not confess. There are four possible outcomes: Frankie and Johnny both confess (cell A), Frankie confesses but Johnny does not (cell B), Frankie does not confess but Johnny does (cell C), and neither Frankie nor Johnny confesses (cell D). The portion at the lower left in each cell shows Frankie’s payoff; the shaded portion at the upper right shows Johnny’s payoff.

Figure 11.6 Payoff Matrix for the Prisoners’ Dilemma. The four cells represent each of the possible outcomes of the prisoners’ game.

If Johnny confesses, Frankie’s best choice is to confess—she will get a three-year sentence rather than the six-year sentence she would get if she did not confess. If Johnny does not confess, Frankie’s best strategy is still to confess—she will get a one-year rather than a two-year sentence. In this game, Frankie’s best strategy is to confess, regardless of what Johnny does. When a player’s best strategy is the same regardless of the action of the other player, that strategy is said to be a dominant strategy. Frankie’s dominant strategy is to confess to the burglary.

For Johnny, the best strategy to follow, if Frankie confesses, is to confess. The best strategy to follow if Frankie does not confess is also to confess. Confessing is a dominant strategy for Johnny as well. A game in which there is a dominant strategy for each player is called a dominant strategy equilibrium. Here, the dominant strategy equilibrium is for both prisoners to confess; the payoff will be given by cell A in the payoff matrix.

From the point of view of the two prisoners together, a payoff in cell D would have been preferable. Had they both denied participation in the robbery, their combined sentence would have been four years in prison—two years each. Indeed, cell D offers the lowest combined prison time of any of the outcomes in the payoff matrix. But because the prisoners cannot communicate, each is likely to make a strategic choice that results in a more costly outcome. Of course, the outcome of the game depends on the way the payoff matrix is structured.

Repeated Oligopoly Games

The prisoners’ dilemma was played once, by two players. The players were given a payoff matrix; each could make one choice, and the game ended after the first round of choices.

The real world of oligopoly has as many players as there are firms in the industry. They play round after round: a firm raises its price, another firm introduces a new product, the first firm cuts its price, a third firm introduces a new marketing strategy, and so on. An oligopoly game is a bit like a baseball game with an unlimited number of innings—one firm may come out ahead after one round, but another will emerge on top another day. In the computer industry game, the introduction of personal computers changed the rules. IBM, which had won the mainframe game quite handily, struggles to keep up in a world in which rivals continue to slash prices and improve quality.

Oligopoly games may have more than two players, so the games are more complex, but this does not change their basic structure. The fact that the games are repeated introduces new strategic considerations. A player must consider not just the ways in which its choices will affect its rivals now, but how its choices will affect them in the future as well.

We will keep the game simple, however, and consider a duopoly game. The two firms have colluded, either tacitly or overtly, to create a monopoly solution. As long as each player upholds the agreement, the two firms will earn the maximum economic profit possible in the enterprise.

There will, however, be a powerful incentive for each firm to cheat. The monopoly solution may generate the maximum economic profit possible for the two firms combined, but what if one firm captures some of the other firm’s profit? Suppose, for example, that two equipment rental firms, Quick Rent and Speedy Rent, operate in a community. Given the economies of scale in the business and the size of the community, it is not likely that another firm will enter. Each firm has about half the market, and they have agreed to charge the prices that would be chosen if the two combined as a single firm. Each earns economic profits of $20,000 per month.

Quick and Speedy could cheat on their arrangement in several ways. One of the firms could slash prices, introduce a new line of rental products, or launch an advertising blitz. This approach would not be likely to increase the total profitability of the two firms, but if one firm could take the other by surprise, it might profit at the expense of its rival, at least for a while.

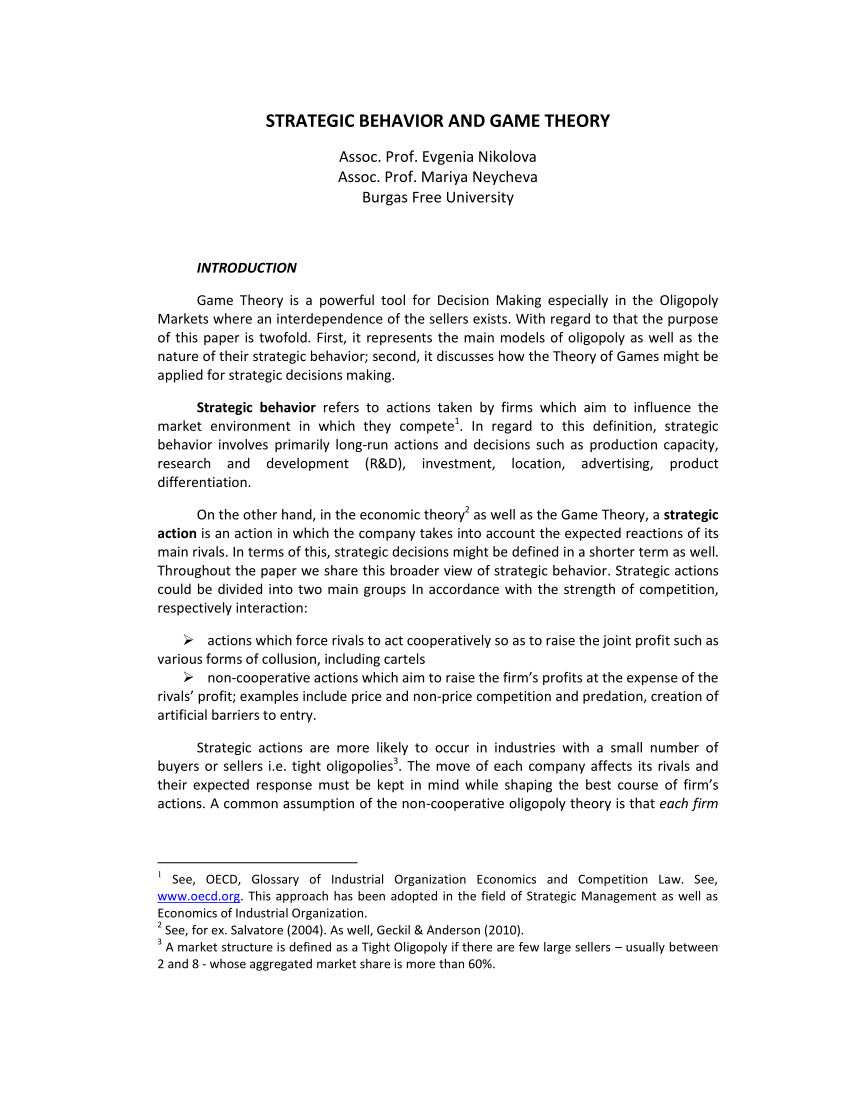

We will focus on the strategy of cutting prices, which we will call a strategy of cheating on the duopoly agreement. The alternative is not to cheat on the agreement. Cheating increases a firm’s profits if its rival does not respond. Figure 11.7 “To Cheat or Not to Cheat: Game Theory in Oligopoly” shows the payoff matrix facing the two firms at a particular time. As in the prisoners’ dilemma matrix, the four cells list the payoffs for the two firms. If neither firm cheats (cell D), profits remain unchanged.

Figure 11.7 To Cheat or Not to Cheat: Game Theory in Oligopoly.

Two rental firms, Quick Rent and Speedy Rent, operate in a duopoly market. They have colluded in the past, achieving a monopoly solution. Cutting prices means cheating on the arrangement; not cheating means maintaining current prices. The payoffs are changes in monthly profits, in thousands of dollars. If neither firm cheats, then neither firm’s profits will change. In this game, cheating is a dominant strategy equilibrium.

This game has a dominant strategy equilibrium. Quick’s preferred strategy, regardless of what Speedy does, is to cheat. Speedy’s best strategy, regardless of what Quick does, is to cheat. The result is that the two firms will select a strategy that lowers their combined profits!

Quick Rent and Speedy Rent face an unpleasant dilemma. They want to maximize profit, yet each is likely to choose a strategy inconsistent with that goal. If they continue the game as it now exists, each will continue to cut prices, eventually driving prices down to the point where price equals average total cost (presumably, the price-cutting will stop there). But that would leave the two firms with zero economic profits.

Both firms have an interest in maintaining the status quo of their collusive agreement. Overt collusion is one device through which the monopoly outcome may be maintained, but that is illegal. One way for the firms to encourage each other not to cheat is to use a tit-for-tat strategy. In a tit-for-tat strategy a firm responds to cheating by cheating, and it responds to cooperative behavior by cooperating. As each firm learns that its rival will respond to cheating by cheating, and to cooperation by cooperating, cheating on agreements becomes less and less likely.

Still another way firms may seek to force rivals to behave cooperatively rather than competitively is to use a trigger strategy, in which a firm makes clear that it is willing and able to respond to cheating by permanently revoking an agreement. A firm might, for example, make a credible threat to cut prices down to the level of average total cost—and leave them there—in response to any price-cutting by a rival. A trigger strategy is calculated to impose huge costs on any firm that cheats—and on the firm that threatens to invoke the trigger. A firm might threaten to invoke a trigger in hopes that the threat will forestall any cheating by its rivals.

Game theory has proved to be an enormously fruitful approach to the analysis of a wide range of problems. Corporations use it to map out strategies and to anticipate rivals’ responses. Governments use it in developing foreign-policy strategies. Military leaders play war games on computers using the basic ideas of game theory. Any situation in which rivals make strategic choices to which competitors will respond can be assessed using game theory analysis.

One rather chilly application of game theory analysis can be found in the period of the Cold War when the United States and the former Soviet Union maintained a nuclear weapons policy that was described by the acronym MAD, which stood for mutually assured destruction. Both countries had enough nuclear weapons to destroy the other several times over, and each threatened to launch sufficient nuclear weapons to destroy the other country if the other country launched a nuclear attack against it or any of its allies. On its face, the MAD doctrine seems, well, mad. It was, after all, a commitment by each nation to respond to any nuclear attack with a counterattack that many scientists expected would end human life on earth. As crazy as it seemed, however, it worked. For 40 years, the two nations did not go to war. While the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 ended the need for a MAD doctrine, during the time that the two countries were rivals, MAD was a very effective trigger indeed.

Of course, the ending of the Cold War has not produced the ending of a nuclear threat. Several nations now have nuclear weapons. The threat that Iran will introduce nuclear weapons, given its stated commitment to destroy the state of Israel, suggests that the possibility of nuclear war still haunts the world community.

Self Check: Game Theory

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered in the previous section. This short quiz does not count toward your grade in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

You’ll have more success on the Self Check if you’ve completed the two Readings in this section.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

Humans are one of the most cooperative species on the planet. Our ability to coordinate behavior and work collaboratively with others has allowed us to create the natural world’s largest and most densely populated societies, outside of deep sea microbial mats and a few Hymenopteramega-colonies.

However, a key problem when trying to understand the evolution of cooperation has been the issue of cheaters. Individuals in a social group, whether that group is composed of bacteria, cichlids, chimpanzees, or people, often benefit when cooperating with others who reciprocate the favor. But what about those individuals who take advantage of the generosity of others and provide nothing in return? These individuals could well thrive thanks to the group as a whole and end up with greater fitness than everyone else because they didn’t have to pay the costs associated with cooperating. For decades the idea that cheaters may in fact prosper has been the greatest difficulty in understanding cooperation as an evolved trait.

However, it turns out that cooperation could be a viable evolutionary strategy when individuals within the group collectively punish cheaters who don’t pull their weight. For example, Robert Boyd, Herbert Gintis, and Samuel Bowles published a paper in the journal Science in 2010 with a model showing how, so long as enough individuals work together to punish violators, each cooperative individual in the group can experience enhanced fitness as a result.

Before understanding how their model could explain the emergence of cooperative behavior it is first important to look at the two leading explanations for the evolution of cooperation: William Hamilton’s (1964) theory of kin selection and Robert Trivers’ (1971) theory of reciprocal altruism.

Kin selection proposed that cooperation will emerge in groups that are made up of close relatives. Hamilton’s rule, beautiful in its simplicity, proposed that cooperation occurs when the cost to the actor (c) is less than the benefit to the recipient (b) multiplied by the genetic relatedness between the two (r). This equation is written out simply as rb > c. Kin selection has been one of the most well tested models that seeks to explain the evolution of cooperation and has held up among such diverse groups as primates, birds, and social insects (though Edward O. Wilson has recently challenged kin selection as an explanation in the latter).

To put this into context: an alpha male lion and his brother share half of their genes, so have a genetic relatedness of 0.5. Suppose this brother recognizes that the alpha male is getting old and could easily be taken down. If so, the brother could potentially have eight additional cubs (just to pull out an arbitrary number). But, instead, that brother decides to help the alpha male to maintain his position in the pride and, as a result, the alpha ends up having the eight additional cubs himself while the brother only has five. The brother has lost out on 3 potential cubs. But, even so, because he assisted his brother he has still maximized his overall reproductive success from a genetic point of view: 0.5 x 8 = 4 > 3. He could have attempted to usurp his brother and, perhaps, had the eight cubs himself but he wouldn’t have been in any better of a position as far as his genes were concerned.

Reciprocal altruism follows this same basic idea, but proposes a mechanism that could work for individuals that are unrelated. In this scenario, cooperation occurs when the cost to the actor (c) is less than the benefit to the recipient (b) multiplied by the likelihood that the cooperation will be returned (w) or wb > c. This has been demonstrated among vampire bats who regurgitate blood into an unrelated bats mouth if they weren’t able to feed that night. Previous experience has shown the actor that they’re likely to get repaid if they ever go hungry one night themselves.

Whereas kin selection requires a community of closely related individuals for cooperation to be a successful strategy, reciprocal altruism requires that individuals be part of a single group, with low levels of immigration and emigration, so that group members will be likely to encounter each other on a regular basis. However, neither model can explain the emergence of cooperation in societies composed of unrelated individuals and where there is a constant influx of strangers. In other words, cooperation in human societies.

The more recent model proposed by Boyd et al. seeks to address this very problem. Their paper posits that fitness is enhanced, not by cooperating with close kin or reciprocating a previous act of generosity, but through the coordinated punishment of those who don’t cooperate. In a social group individuals are able to choose whether they want to cooperate or defect. Suppose, for example, that a hunter returns from a successful hunt and must decide whether or not to share their gains with other members of the tribe. According to Boyd’s model, the cost to the cooperator (c) is less than the overall benefit (b) but is still greater than the benefit to each member of the group (n): b > c > b/n. If the hunter chose to cooperate, the meat would be divided so that everyone benefits but the hunter still enjoys a slightly larger share. They would also receive a benefit in the future when other hunters had more success than they did (just as they would under reciprocal altruism).

However, if the hunter refuses to share with other members there are two stages to contend with. The first is the signaling stage in which individuals signal their intent to punish those who refuse to cooperate. This is a common occurrence not just in humans but in many animals, especially primates. Baboons, for example, use threat signals such as staring, eyebrow raising, or a canine display to warn others to change their behavior. In humans this can take a variety of forms including angry looks, hand gestures, and/or harsh words. The cost of such signals are fairly low, but still high enough that it doesn’t pay to signal and fail to back it up with action if necessary.

If the warning doesn’t provide the appropriate result the next stage is coordinated punishment. According to Boyd’s model a quorum (τ) of punishers is required to work together to target an individual who refuses to cooperate. In such cases there will be a cost (p) to the target and an expected cost to each punisher of k/npa, where np is the number of punishers. Given that an outnumbered target is unlikely to inflict costs on the punishers, the model assumes that a > 1. What this means is that the higher the number of punishers, the lower the cost to each involved. Furthermore, the punishment doesn’t necessarily involve physical attacks. The model allows for punishment to come in the form of gossip, group shunning, or any other nonaggressive action that brings a cost to the uncooperative target.

According to this model a society would be made up of some combination of punishers Wp and nonpunishers Wn. If there were only a single punisher in the group (τ = 1), what is known as the “Lone Ranger” condition, the fitness cost would outweigh the benefit and punishers would decline in the population. However, for larger values of τ punishment does pay and therefore increasing the number of punishers increases their fitness.

The Cheating Or Cooperate Game Show

This model has had some empirical support. For example, last year Boyd and Sarah Matthew found that punishing desertion promoted cooperation in raiding parties among the Turkana pastoralists in East Africa. Likewise, Lauri Sääksvuori and colleagues published their results in Proceedings of the Royal Society suggesting that this form of enforced cooperation could emerge through competitive group selection. While further empirical tests are needed to confirm Boyd's model, it has the benefit of demonstrating how cooperation could evolve even in large societies where kinship is low and immigration is high: the very factors that were previously thought to confound the evolution of cooperation.

The Cheating Or Cooperate Game Changer

However, given that many indigenous systems are based on restorative justice (in which offenders are brought into a relationship with the victim and must make restitution to regain the society’s trust) it’s unclear how accurate a model focusing exclusively on punishment would be for understanding the evolution of human cooperation. Nevertheless, Coordinated Punishment now joins other recent approaches, such as Generalized Reciprocity, that seek to reexamine how the common good could emerge out of the selection for individual fitness.

The Cheating Or Cooperate Games

Reference:

The Cheating Or Cooperate Games On

Boyd, R., Gintis, H., & Bowles, S. (2010). Coordinated Punishment of Defectors Sustains Cooperation and Can Proliferate When Rare, Science, 328 (5978), 617-620. DOI: 10.1126/science.1183665

This post has been adapted from material that originally appeared at ScienceBlogs.com.